Until the last few years I had what was very nearly an aversion to short stories. As one reader friend of mine says, they are tempting, but just as you get sucked in, the story is over. So if the stories are good, they leave you wanting more, and if they are not so good, seem simply a waste of time. Passing time instead of really reading.

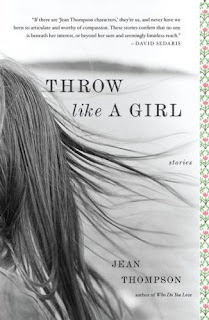

Until the last few years I had what was very nearly an aversion to short stories. As one reader friend of mine says, they are tempting, but just as you get sucked in, the story is over. So if the stories are good, they leave you wanting more, and if they are not so good, seem simply a waste of time. Passing time instead of really reading.Had it not been for incredible writers like Grace Paley, Alice Munro, Elizabeth Strout, and Carol Shields, I may still have shunned short fiction, and thereby missed out on reading Jean Thomson. Like the above writers, Thompson writes about us, ordinary people neither rich nor famous. But unlike Munro and Strout, Thompson’s characters are mostly city folk very much caught up in the now of frenzied city-life, economic insecurity, bleak predictions, abandoned hopes.

Almost all the stories are in a very intimate first person, inside the mind and body of the narrator immediately. I could easily review the book simply by giving first lines of stories. Each announcing a character and set of circumstances all of us readers recognize, sometimes with a sigh or in-taking of breath, sometimes with the nod of the head. “Jack Pardee signed his enlistment papers in May, right after graduation. The Army recruiter had been working on him for most of a year.” Her story “Lost” begins:

I was twenty years old and about as pretty as I was ever going to be, although I didn’t know that yet. I had long long hair, all the girls did. Mine was nearly down to my waist. It swung across my back like a bell. I had nice legs. There was always some boy I was crazy for, always trouble with some boy. There was never any useful purpose to it. I could never figure out what to do with them, besides wanting them to distraction.

You wanted so badly to believe that life was basically good, that people were basically good. And Mrs. Colley did believe it. She might not go around announcing that she was wonderful and blessed, but she reminded herself often that there were many terrible places she could have been born into but had not. Nothing abnormally bad had ever happened to her personally or was likely to happen except for, eventually, dying, oh well. But nowadays there was so little you could trust to stay good, as if there was a pinhole at the bottom of the world and all the best things were leaking out of it.

At one point in the story Janey, who has been newly initiated to sex, asks Gail if sex is supposed to hurt. And after a few stumbling attempts to get at what is behind the question, Janey blurts out, “I think he was trying to make it hurt.”

That made me queasy, I guess it shocked me. We didn’t like thinking of ourselves as vulnerable, breakable, controllable objects, even if that was exactly the way some people saw us. I said that it wasn’t right, what he’d done, and she said, Yeah, she knew. But she was still mulling it over, keeping something back. “What?” I said.

“I let him think I kind of liked it.”

I didn’t want to hear that either. Because I understood why girls did such things, even a bold, harum-scarum girl like Janey, understood why we went along with so much, were anxious to please, laughed when nothing was funny, kept silent when we should have spoken, bent ourselves into obliging shapes, did the things that shamed us, even as Janey was ashamed. There was some desperate and unlovable creature that lived inside us, and we had to keep it fed.

I had two daughters and a husband who didn’t notice things. I was lonesome. Sex isn’t always about sex.

My husband was no trouble. Never had been. I’d grown used to stepping over and around him the way you might a large dog sound asleep in the doorway. You start out being married together and you end up being married apart. I’m convinced that’s the truth for most people, if they were honest about it.

She hated her mother and she hated her father to, at least when he was around to be hated. She hated school and all the snotty girls who put their heads together giggling and talking big and showing off their nail polish and their new shoes and new cell phones and whatever else they bought bought bought.